Triangle of Sadness sails into bold new waters

The scathing satire explores class in the macro and the micro

Woody Harrelson’s sea captain - American, apathetic, and anti-capitalist - intellectually spars with Zlatko Burić’s Russian oligarch aboard a superyacht for a luxury cruise during an intense storm. Ideologically opposed, they toss famous quotations back and forth, arguing for their convictions via proxy. As their words flow, so do their drinks, making a chaotic situation during this turbulent storm even more unpredictable; at one point, Burić’s character commandeers the PA system to inform everyone that the ship is going under, a drunken fib for his amusement. Between such pranks and pounds at the door by the first mate, Harrelson’s character becomes solemn, recognizing his own hypocrisy amongst his many possessions; as he drunkenly puts it, “I’m a sit shocialist. I have too much.” Before disappearing for the rest of the film, Harrelson offers this moment of introspection, the only such moment by any of the characters in Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness. The title refers to a term used by plastic surgeons to describe the worry wrinkle that occurs between the eyebrows, which can be fixed with Botox in 15 minutes. Fittingly, this is a story of anxiety hidden away behind decadence, wealth, and power, and Östlund explores these ideas to craft yet another sharp satire, a scathing critique of the elite, and a meditation on the human need to have too much.

Often it is the case that satires such as these suffer a righteous superficiality, making pointed observations for their own sake at the expense of cinematic essentials like narrative and character development. But Östlund crafts his world and characters organically; his observations are certainly pointed, but there is a degree of subtlety that steers the film away from accusations of preachiness. These are real human beings, however cartoonish they may be, going through real human struggles. The macro class conflict casts a shadow over every scene, but it is the micro conflicts between characters that give the film texture. The ideas explored are best expressed when these two conflicts, macro and micro, intersect in interesting ways. As the film reaches its heart pounding climax in its last few moments, this intersection becomes thrillingly apparent and effective.

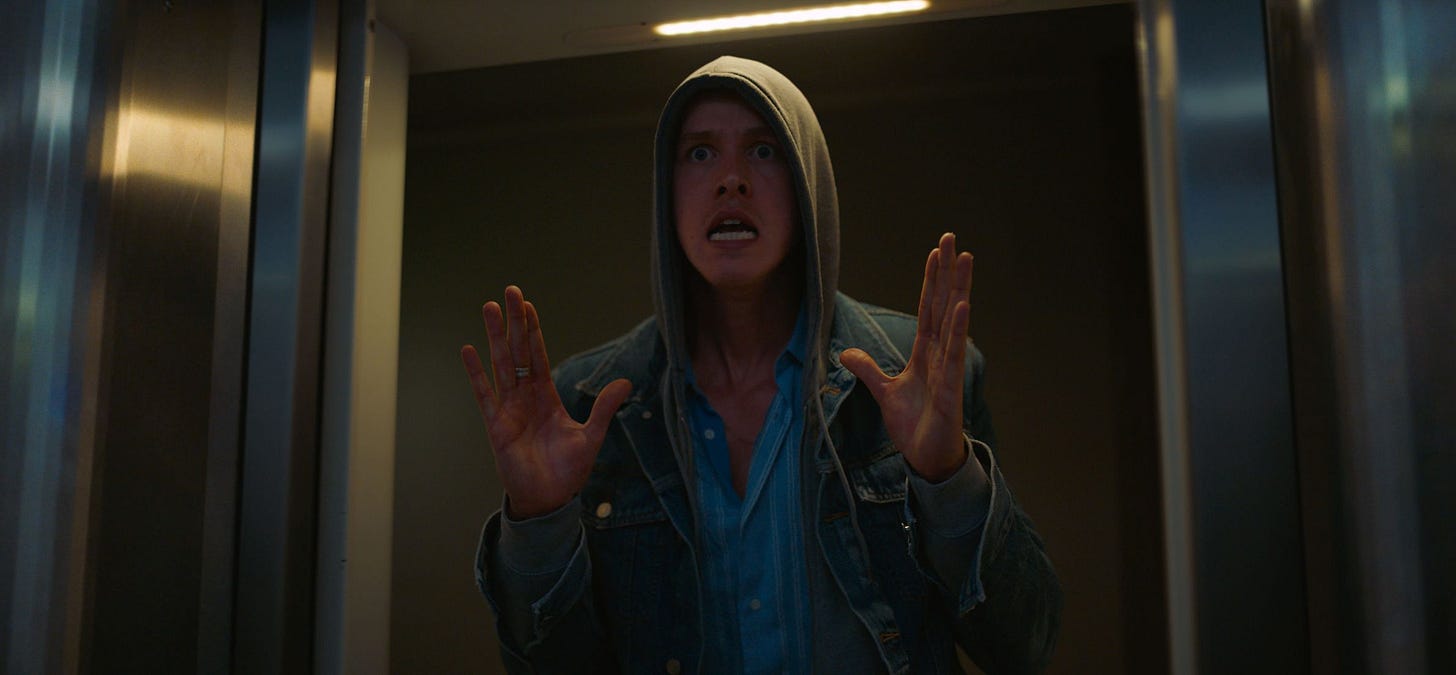

The film’s primary novelty is its upending of expectations, flipping the script on economic, gender, and racial inequality. The ultrarich are attended to by an eager-to-please white staff, representing society’s middle class, desperate for the elusive bonus from their gracious patrons. This group serves as a buffer between the guests and the non-white staff in the lower decks performing the menial tasks. But when the ship sinks (Östlund spoiled this years before the film even came out, so I don’t think a spoiler warning is necessary), and a few survivors from each strata make their way to an island, it is Abigail, a woman of color and a toilet cleaner, who takes power due to her useful hard skills that none of the rich have. These events put into clear focus what constitutes real value, in contrast to what very little the wealthy and powerful actually contribute to society. There is a wide ensemble of wonderfully acted characters that help paint this picture, but our protagonist Carl acutely illustrates these conceptual positions. A struggling male model who makes less than his more successful model/influencer girlfriend Yaya (played wonderfully by the late star-in-the-making Charlbi Dean, who tragically passed away late this summer), Carl represents the insecurity and anxiety endemic to young men facing late stage capitalism and a crumbling patriarchy. When the power dynamics change, he does what he has to do to maintain a sense of security and stability, no matter the cost.

Condensed into a text summary, the narrative itself is nothing groundbreaking, save for a few twists and turns. Structurally speaking, the plot is somewhat uneven - we don’t even get to the island until more than halfway through the story - but the film is never boring. Östlund operates with complete control of his pacing, slowly building out the world, setting the stage for his conceptual gut punches. There are long stretches where we completely forget about our main character, but this time is devoted to developing a mosaic of images and ideas that find new meaning by the end.

When discussing it alongside Force Majeure and The Square, Triangle of Sadness represents a continuum for Ruben Östlund; in this reviewer’s opinion, his films have only gotten better, innovating with story and form while maintaining an interest in human nature under pressure. His work isn’t perfect by any means, but he presents such a strong artistic voice that it’s hard not to listen. The 2020s will be remembered for many incredible films and the masters that made them, and this film and Ruben Östlund will certainly be one of them.

As Östlund’s films have improved so have your reviews! One of your most insightful ones yet!