The Boy and the Heron visually stuns but disappoints

Miyazaki's latest film is a triumph - but only if you've already bought into him

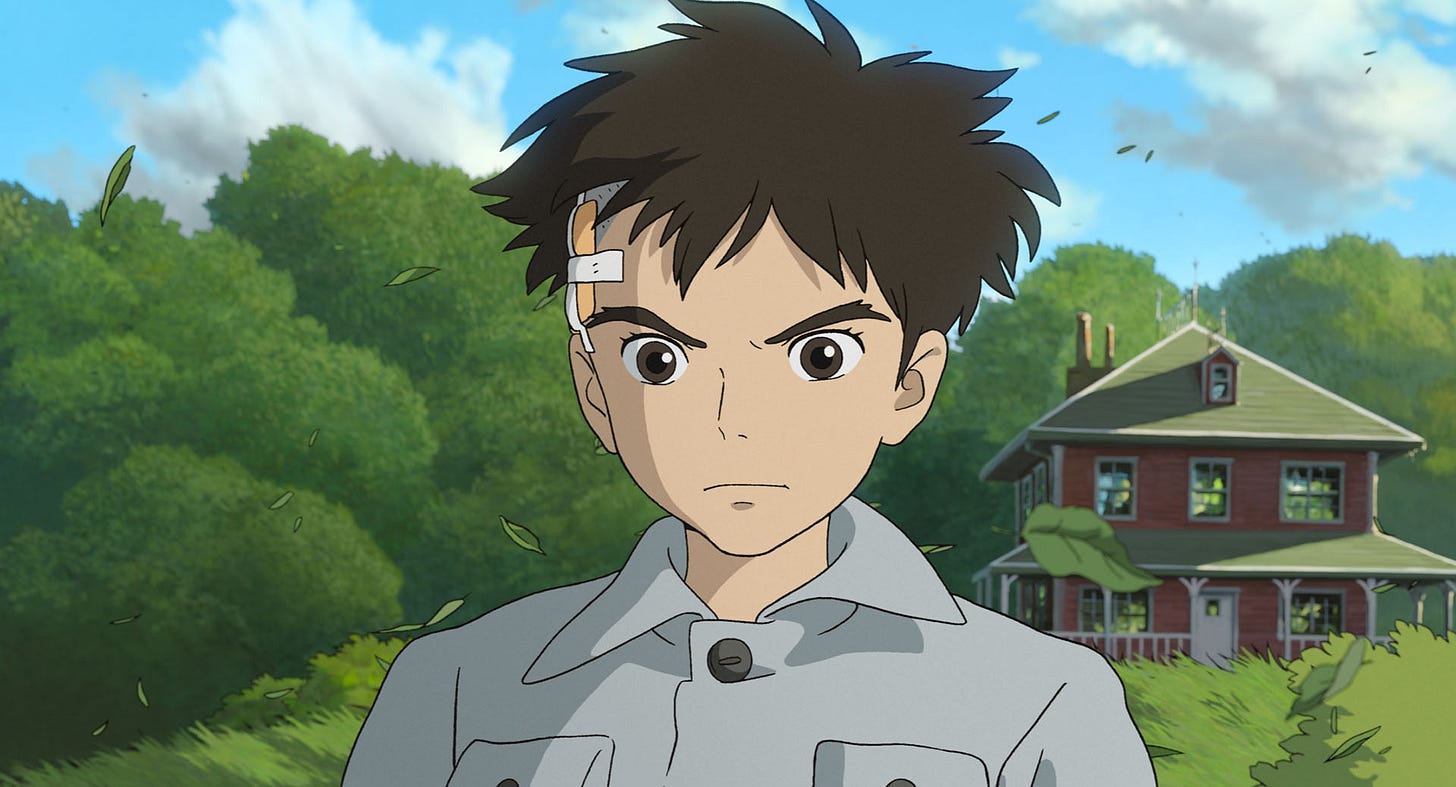

There’s a persistent fear of mine that I’m sure many other critics share - how influenced are my opinions by critical consensus? Do I only love a given film because others do as well? Am I harsher on a universally-panned movie than I would have been otherwise? It’s a legitimate concern, one that I am ever vigilant against to ensure the sincerity of my perspective. But then I’ll watch a seemingly-universally beloved film and be reassured of my own intellectual integrity; Hayao Miyazaki’s work has consistently proven to be an appropriate means to test this integrity. His filmography, even its lesser entries, seems to inspire dogmatic acclaim from cinephiles and critics alike. Unfortunately, my mileage with his films have varied. I love Princess Mononoke for its epic fantasy narrative and Kiki’s Delivery Service for its simple yet effective character exploration, but Studio Ghibli’s remaining output (of which I admittedly have not seen all) often fails to resonate with me beyond admiration for its animation. Needless to say, I was very trepidatious about The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki’s first film in a decade and quite possibly his last. Would I finally find the secret to appreciating this wildly influential filmmaker? Disappointingly, the answer to this question is still no, and his latest film doubles down on everything that people love about his films, leaving me in the same place as I was before.

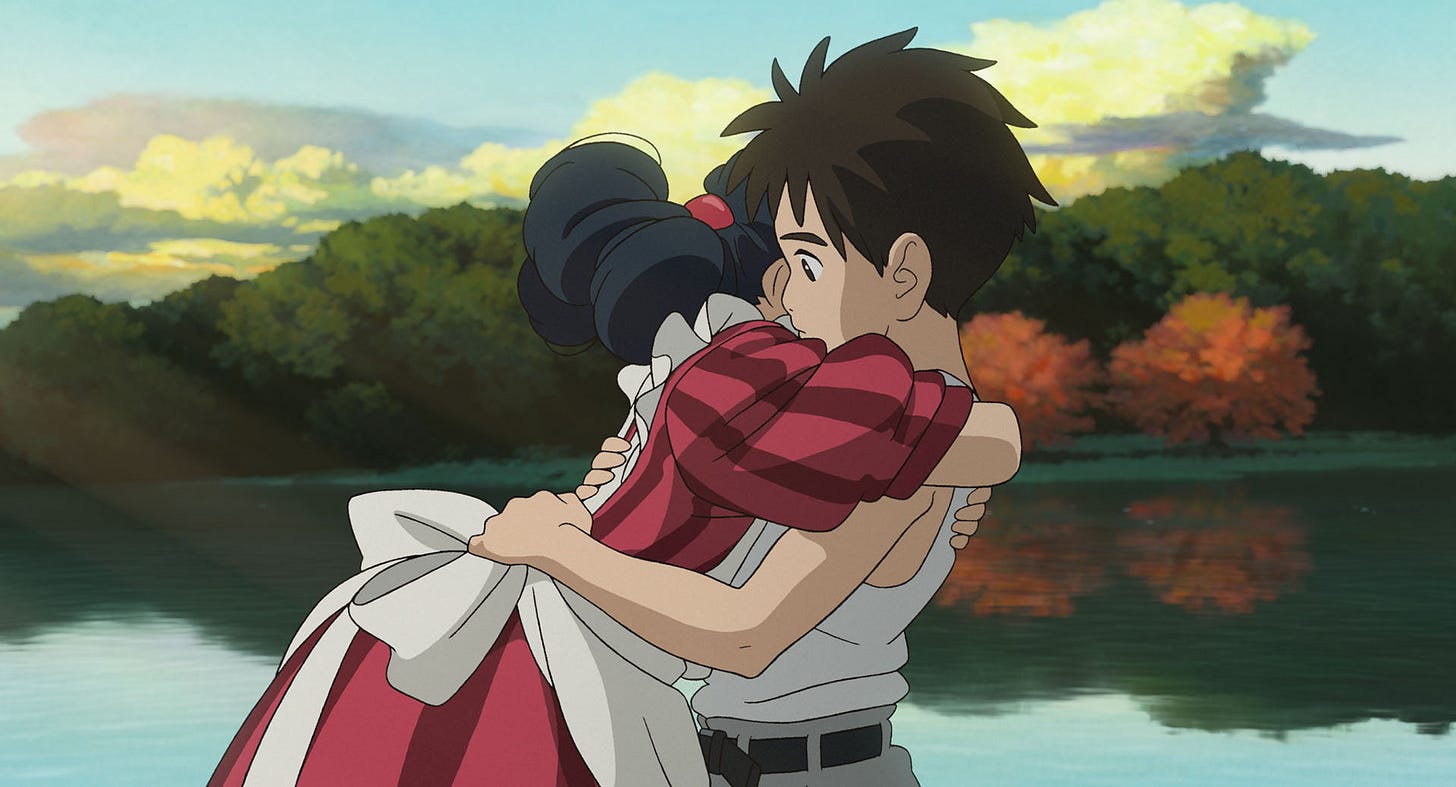

But what exactly is wrong with this film - or with any of Miyazaki’s acclaimed masterworks such as Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle? I find it difficult to articulate my position clearly, as there are few major sources of similar discontent to help crystallize my perspective. After years of reflection, however, the issue seems to be in scripting - or lack thereof. Studio Ghibli films are often characterized as fantastical dream odysseys, maneuvering through pure imagination in ways just too profound for inexperienced Western audiences to appreciate. This supposition heavily relies on the idea of dream logic - the search for literal meaning in these films is a fool’s errand and completely misses the point, critics would say. But I reject this hypothesis, which conflates bullets in a plot outline with genuine human drama. Some of my favorite films - Mulholland Drive; Synecdoche, New York; and Beau Is Afraid - are all deeply rooted in a dream logic that rejects classical expectations of realism. But in all three of those films, even if we don’t fully understand what is going on, we always understand why it is happening, or more importantly, what it means for the characters. Motivations in these films, while obfuscated by bizarre story machinations, are ultimately clear, even if implicitly so, in ways that Miyazaki seems explicitly disinterested in exploring. Characters in his films are vividly realized in terms of their designs, characterizations, and performances (both Japanese and English alike), but I struggle to connect with either them or their plights.

The resulting lack of character depth (at least, in ways that make for a satisfying character-driven narrative) results in a meandering storyline that whimsically transitions from one strange unexplained setting to another, rarely coalescing into anything more meaningful. The lack of clear character motivations (or a deeper subconscious understanding of those motivations) renders this film’s protagonist Mahito ill-defined and passive, shuffling through a plot that seems more like an afterthought to accommodate visual ideas. Once again, Miyazaki leaves me cold - what exactly is this story about? Perhaps that is a reductive question, but what really rests in this film’s heart? What does Miyazaki want us to take away from his film? How does it inform our understanding of the human condition? The aforementioned notion that Japanese films aren’t as concerned with plot and logic as American films seems to disregard a host of Japanese films and filmmakers that do prioritize character realities and thematic ambitions. It feels disingenuous to suggest that Japanese films aren’t concerned with such things when Godzilla Minus One, also originating from Japan, is one of the most emotionally affecting films of the year.

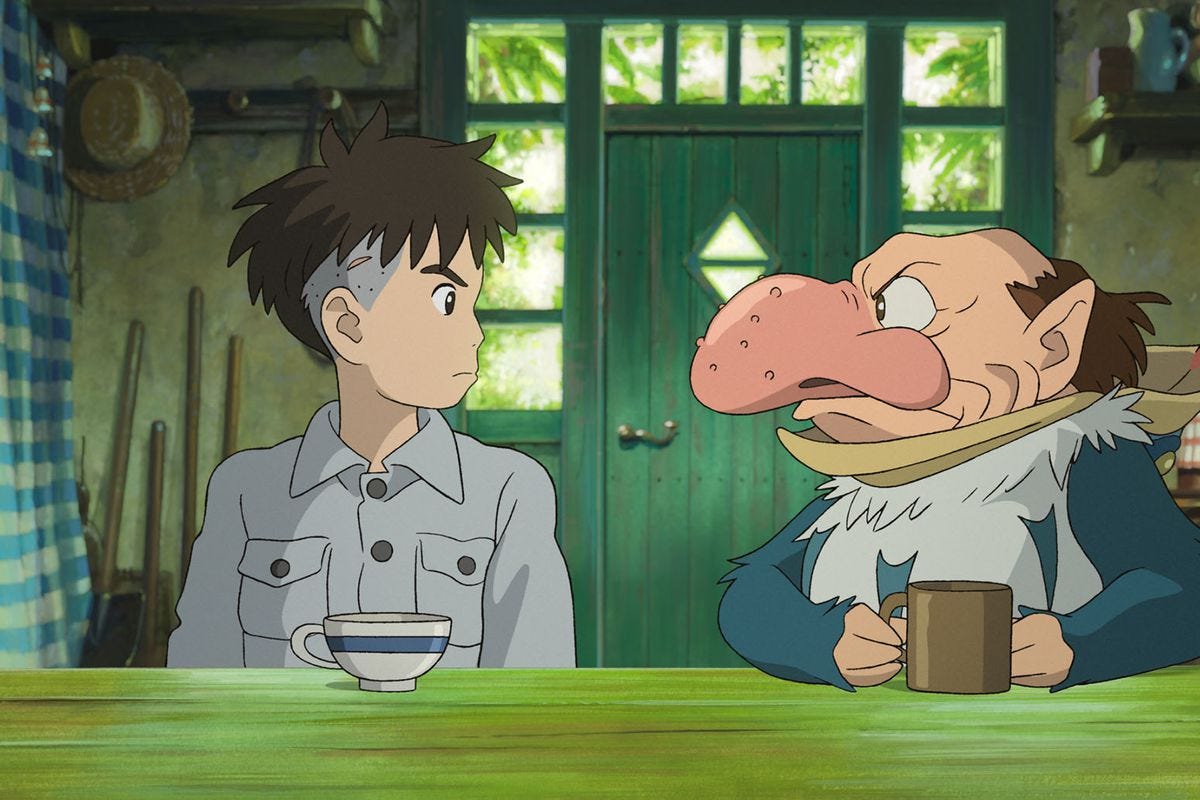

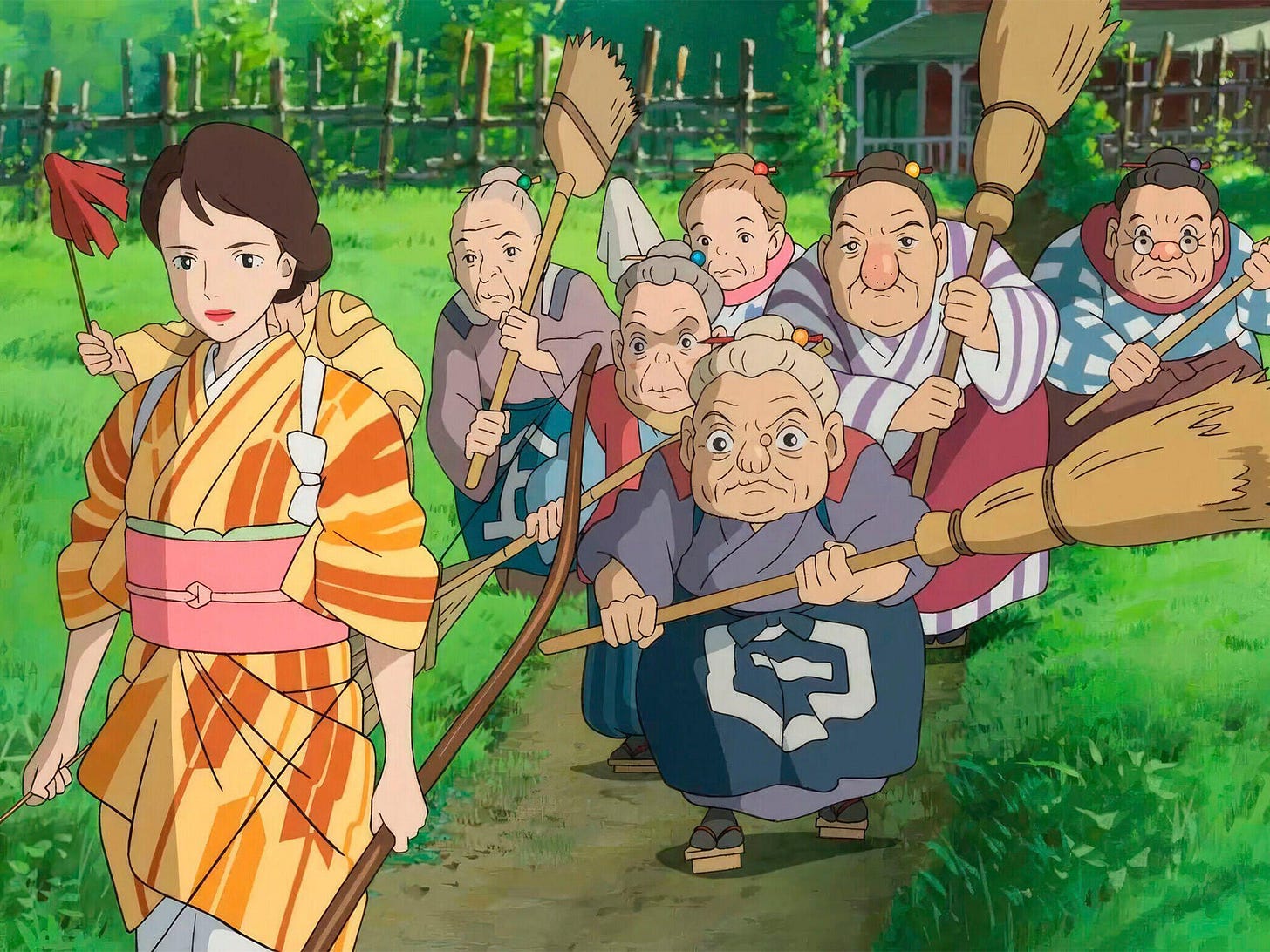

But even I can admit that these critiques, perhaps, are unfair. This one film shouldn’t receive the full frustration that I hold for an entire filmography. Furthermore, I should attempt to meet this film on its own terms. As always, Studio Ghibli’s visual style is stunningly gorgeous, and seeing the film on the big screen reinforces Miyazaki’s place in the annals of animation history. For better or for worse, this is Miyazaki’s singular vision made manifest once again, and the film can at times feel like a greatest hits showcase. Medium-defining animation? Check. Acute connection to nature? Check. Adorable (and merchandisable) creatures? Check. Condemnation of war and militaristic inclinations? Check. Elderly characters with preposterously large red noses with boils? Surprisingly, check. But I found the film most interesting when it defied expectations of Miyazaki’s work. I found the opening scene captivating, bringing the horrors of American firebombing campaigns to vivid life, but…what is it all for? War and trauma clearly play a thematic role, but aside from simple explanations or extrapolated ones, the film struggles to make itself known on a more intimate level.

Perhaps the world has pulled an elaborate prank on me. Maybe everyone hyping up The Boy and the Heron does so to intentionally mislead me. Such paranoia is obviously a joke on my part, but when I read reviews for this film or for much of Hayao Miyazaki’s work, I find myself wondering if I have entered into an alternate reality, a Twilight Zone-esque social tragedy where I’m unable to appreciate that those around me find immensely beautiful. But however much easier it would be, my thoughts are my own - I can’t force myself to love this film. Based on this review, you’d probably think that I hated it, but I wouldn’t categorize my stance as such. The film is easily a net-positive experience, an impressive feat of filmmaking to be sure - I just can’t help but feel frustrated watching it - and I’m frustrated at myself for being blind to what everyone else can easily see. But at least my critical resolve is healthily independent.

Peter, if you want a Ghibli film that puts ALL the focus on character PLEASE watch "The Tale of the Princess Kaguya." Directed by the other acclaimed Ghibli director, Issao Takahata, I feel like every criticism you have of Miyazaki's filmography is corrected here while never compromising on the beautiful visuals as well.