Oppenheimer defies even the loftiest expectations

Christopher Nolan expertly balances a myriad of influences and inspirations

My first introduction to IMAX 70mm film was back in the summer of 2017; I went to see Dunkirk at the IMAX theater in Providence, one of only 30 in the world capable of projecting this premium film format. I probably hadn’t seen a film projected on film *at all* since the practice was phased out for more reliable (if less dynamic) digital projectors about a decade earlier, and I had grown dubious of the fetishization and idolization of “film,” a pervasive fixation of “film bros” at Tisch. But this was different - the colors were rich, the clarity outshined the best 4K televisions, and the intensity of the sound was matched only by a screen six stories tall, well beyond my peripherals. Easily Nolan’s most visual film, Dunkirk proved to be an incredible demonstration of this format’s power and cinema’s potential. I quickly became a film evangelist, particularly for IMAX 70mm, its expanded aspect ratio, arguably vertical in nature, stretching into the heavens. To my mind, every film should be made this way, yet many disagreed, citing the format’s strength as a weakness: it’s great for big movies, but it wouldn’t work for smaller stories. This perspective feels terribly shortsighted; the texture of the human face, framed with portraiture proportions, blown up to over 75 feet tall, produces a level of uncanny intimacy. That being said, Dunkirk, a high octane battle for survival, wasn’t the best showcase for this theory (and I didn’t see Nolan’s Tenet in theaters due to the pandemic). But finally, six years later, I’ve been vindicated by Oppenheimer, a three-hour interpersonal-political-thriller-epic-tragedy that prioritizes the humanity at the heart of history - to great success.

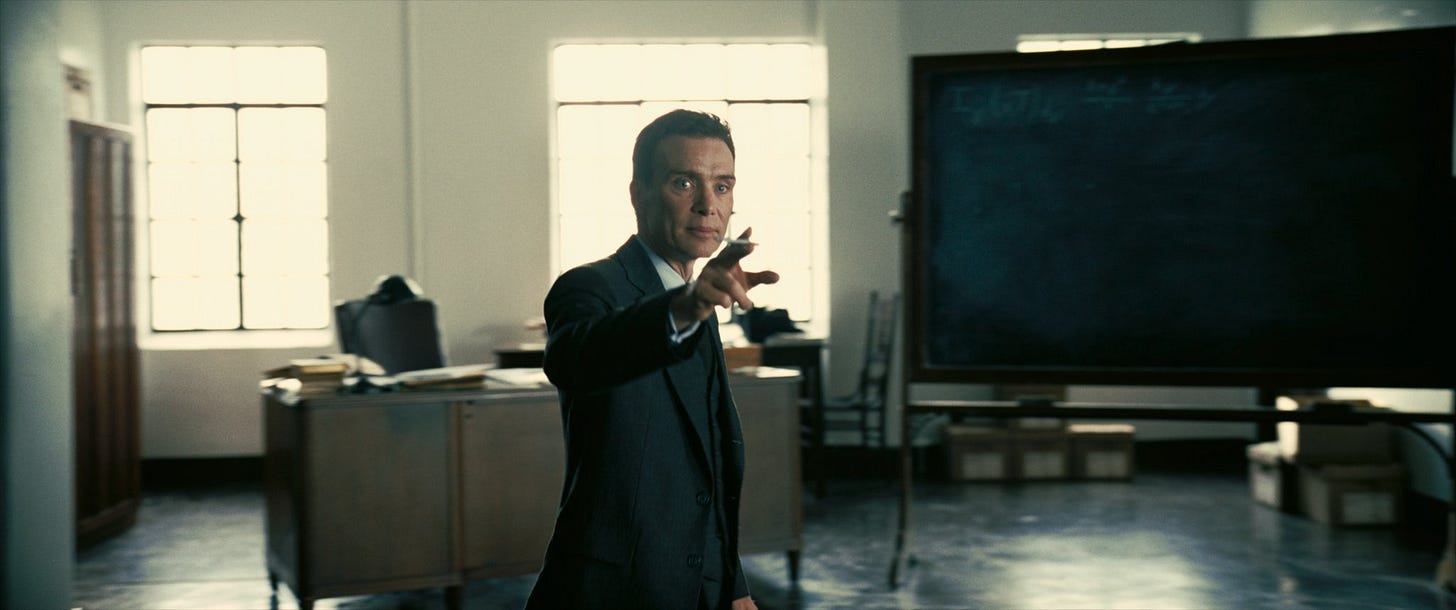

There are certainly plenty of moments here that fit the classical ideal of what IMAX is “best” for, but Nolan’s latest masterwork primarily concerns itself with people just…talking. There are no exhilarating chases through the streets of Gotham; there are no mind-bending dreams brought to life; and there are certainly no trips backwards through time, as much as this film’s protagonist wishes there were. In a story where dialogue is action, Nolan presents scenarios with his trademark intensity and momentum. But this is only fitting - after all, these aren’t just any conversations, but ones with historical gravitas so great that it’s amazing that they don’t collapse in on themselves. The filmmaking on display here is nothing short of epic - a whispered conversation between lovers holds the same drama as the detonation of the first atomic bomb. These are not two sides of the film - the macro and the micro - but rather codependent parallel experiences that warrant the same level of interest. But again, it’s the human face - not the bomb - that’s the real star of the film, enhanced by IMAX 70mm film.

But statistically speaking, most people who see this film in theaters won’t get this experience, and the film needs to stand on its own merits beyond any specific exhibition qualities. I was lucky enough to see the film twice, both in IMAX 70mm, but there’s enough here to make for one of the best films of the year, if not the decade, even if watched in the humblest of home settings (just don’t watch it on your computer or phone, okay!?). The film is not as aesthetically inventive as I was hoping for, to be sure, but this is certainly Nolan’s most subjective and expressionist film to date. Characters' fears, guilt, and shame occasionally come to visual life, pushing the boundaries of reality to arrive at a deeper, more fundamental truth beyond what meets the eye. Such moments are wonderful salves for Nolan’s characteristically expository dialogue - one never needs to wonder what a character is thinking, as they’ll almost inevitably always say it point blank. Nolan’s writing style, coupled with the dense subject matter, could have yielded a more arduous experience, but casual moviegoers will be able to follow just enough of the plot machinations thanks to some stellar performances.

Cillian Murphy has always been a bridesmaid in Nolan’s filmography, but after nearly two decades of collaboration, he finally gets to be the bride. Easily one of the best actors of his generation, Murphy turns in what will most certainly garner him a nomination, if not an outright win, for Best Actor during awards season this winter. Possessing an uncanny resemblance to Oppenheimer, his piercing blue eyes implicitly communicate a brilliance and charisma authentic to the real-life figure. He’s contrasted by Lewis Strauss, the awkward, vindictive bureaucrat brought to life by Robert Downey, Jr. While his performance has been a bit overhyped by critics (this is the first time that he has really been able to act in years, to be fair), Downey delights in playing the man responsible for Oppenheimer’s downfall. The film tries to paint this dynamic as a 50/50 animosity, though Strauss is disappointingly disproportionately absent for most of the story, leaving this thread to almost feel like an afterthought.

With so much historical and thematic material to cover, maybe this film should have been - dare I say - even longer. Nolan’s work is typically on the longer side, yet his editing is always brisk, borderline breakneck, as if he cut ANYTHING that wasn’t absolutely necessary (like dramatic beats). To that end, the best moments are those that settle into themselves, that give the audience breathing room to reflect and draw their own conclusions. Nevertheless, because of its pacing, the film is never boring and always engaging - so engaging, in fact, that I wish Nolan would let me focus on moments for just a little bit longer! But the film is neatly divided into three major sections: building the man, building the bomb, and tearing everything down. A truly fascinating historical figure, Oppenheimer’s story gives way to a natural tragic arc - the epic rise and the inevitable fall. Again, Nolan has made a surprisingly personal film, and while the third act stakes - whether or not Oppenheimer’s security clearance will be renewed - are nothing compared to nuclear Armageddon, they feel just as important.

It’s really that last third that pays off essentially two hours of narrative and emotional set-up. In many ways, the security clearance hearing represents more than one man’s access to government secrets; it’s a battle for the soul of America and the direction of its future. Nolan’s films are rarely political beyond broad metaphor, so it was a pleasant surprise to see just how political the film was; or rather, how specific it was in its politics. His films often capture a general political zeitgeist, but due to the nature of this story, overt measures are taken to draw explicit lines in the sand. American flirtation with socialism during the Great Depression becomes a liability during the Red Scare of the 1950s, as Oppenheimer proudly corrects an accusation of being a suspected Communist by declaring himself a New Deal Democrat. The shifting sands of American political ideology prove to be unstable ground for the species-level threats that America faces following the war with Germany and Japan. The film isn’t leftist, per se, but it’s certainly critical of American hostility towards leftism, especially when it results in a bellicose foreign policy, disruption of foreign democracies, and a discrediting of outspoken dissidents.

Yet despite covering events reaching as far back as a century ago, the film is viscerally relevant to modern audiences. Nuclear war with Russia, something that seemed unthinkable after “The End of History,” is more likely than it has been in decades. Old concerns renew themselves, but new ones creep steadily in the background; many observers note a new Cold War blossoming with China, a conflict that could prove even more catastrophic than the tension with the Soviet Union thanks to new technologies like cyberwarfare and artificial intelligence. The latter may prove to be the most analogous to the atomic bomb - both are technologies that we can’t begin to fully understand the implications of, and that strike fear in the hearts of their creators. The film challenges us to wrestle with these questions: how far can science go, and how far should it go? Unfortunately for us, there’s no easy answer to either of those questions, but it’s in the asking that brings us closer to the truth.

With so many intellectual, thematic, and historical considerations, it’s amazing that the film is able to resonate at all. Nolan has always struggled with emotion; critics often paint his films as cold, calculating, and aloof (in no small part due to his films’ pacing), but this characterization feels unfair. It’s not that his films lack an emotional core - rather, he places human emotion at a distance, almost Brechtian in nature, to accommodate his typically dense storylines. Perhaps one could compare such an experience to reading a Greek myth, its characters behaving archetypically rather than authentically. But unlike Nolan’s other films, this approach works best here since Oppenheimer himself was rather distanced and aloof. Again, the subjectivity here is key: apparently, Nolan even wrote the screenplay in first-person perspective of Oppenheimer, so it’s only natural that the film reflects how he sees the world.

But because of that subjectivity, there are many topics and communities left to the margins. Nolan’s films have always been centered on white men, but it’s most justified (if one can justify such a thing) here since, frankly, there weren’t all that many women or people of color involved in the most important military project in the 1940s. Emily Blunt plays Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty brilliantly, but she doesn’t get all that much to do, though her big scene - you’ll know it when you see it - is a standout of the entire film. Florence Pugh is even more underused as Jean Tatlock, a Communist and Oppenheimer’s first love. But Pugh, like Murphy, is one of the best actors of her generation, so she’s able to leave an indelible mark on both Oppenheimer and Oppenheimer. But the focus is still (somewhat understandably) on white men, with little to no regard for the Japanese perspective. Again, if the film is meant to be viewed through Oppenheimer’s eyes, this makes sense, as there was probably little to no regard for anything besides creating the bomb as fast as possible. That being said, the film’s central ideas would have been benefited by at least seeing photographs or film reels of the effects of the bombs on Japanese citizens that survived - there is already a scene where an audience of scientists views such photos, but perhaps Nolan wanted to leave the bomb’s impact to the imagination. Nevertheless, there are still plenty of instances where the callousness of American foreign policy is on full display if you’re actually thinking critically, and anyone who says that this film glorifies the bomb or ignores the moral implications of its use either hasn’t seen the film, is acting in bad faith, or needs to take a media literacy course.

Oppenheimer is a gargantuan film that’s trying to balance a host of intentions; it’s got the Nolan dialogue and editing style of Inception, the thrilling political battles of JFK, the rivalry of Amadeus, and the epic visuals of a mid-century David Lean epic. The film is interpersonal, exhausting, mammoth, beautiful, horrifying, and political. It wants to explore the mistakes of the past for us in the present to chart a better future. On the whole, Christopher Nolan is more or less able to balance all of these different influences and interests - but just barely. After my first viewing, I felt that, while great, the film was never more than the sum of its parts, lacking some “je ne sais quoi”. A second viewing helped me see more clearly that connective tissue, and the pieces really start to fall into place once you understand where Nolan is going with all of this. Perhaps a third viewing would reveal further insights, sparking further conversation. When I went to see the film a second time, now with my fiancé, we didn’t leave the theater until about 2:00 in the morning, yet our trip home on delayed subway trains was filled with electric discussions on the film, its artistic merits, its historical revelations, and its philosophical implications. I’d be hard pressed to think of a movie that has had that kind of impact, and I don’t think we’ll see another like it for a long time.

I totally agree with everything here Peter. After my first viewing I was left speechless unable to say anything except "yeah we could go do dinner."

I particularly liked how the film uses Nolan's weakness in the emotions department to it's advantage. As a scientist, the character of Oppenheimer feels like he is above feelings and other human considerations. He sees the natural laws holding everything together and has the knowledge to know how to manipulate it any direction he wants. It's not until the bomb drops on Japan that he realizes how wrong he was and how little control he really has, which opens the flood gates for the last hour to just pummel him with all the thoughts and feelings he avoided through the first two.